WRITTEN BY ANU KHOSLA / PHOTOGRAPHED BY ANDREA CAMPOS

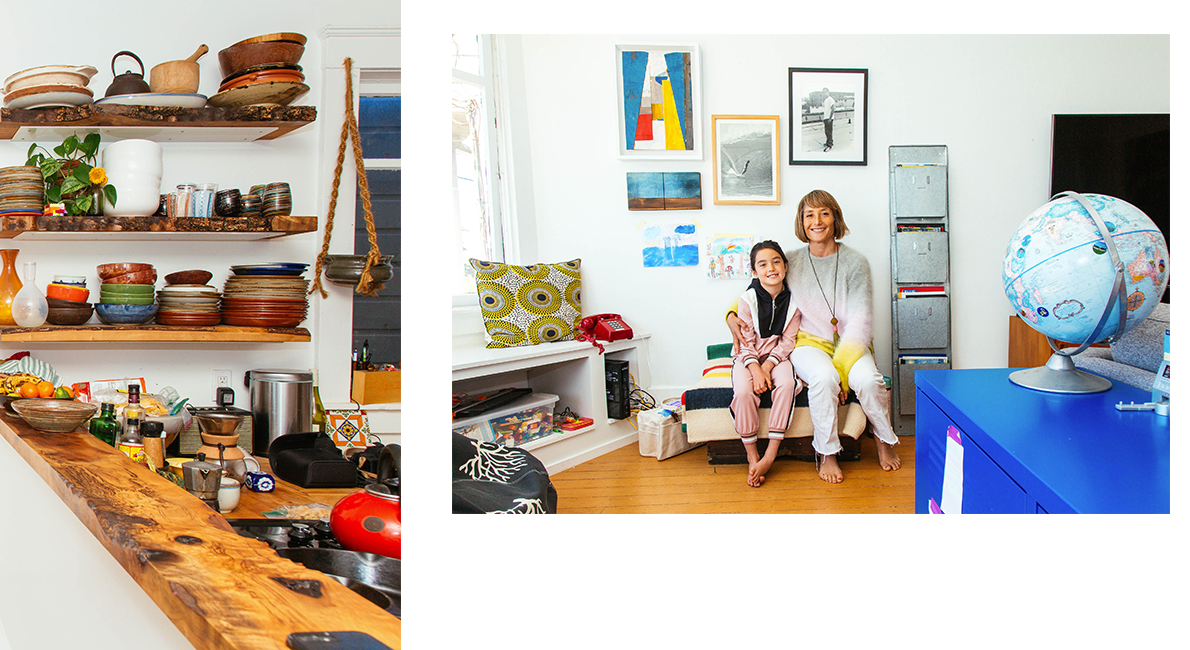

Sachi Cunningham

MULTI-MEDIA JOURNALIST, FILMMAKER, EDUCATOR, SURFER

“My white dad was, I think, more the tiger mom of the family.”

When Sachi Cunningham moved to San Francisco in the early 2000s she, like many surfers before her, chose to live in the Outer Sunset. I suppose no one had warned her about the heavy summer fog. Her boyfriend had been away in Indonesia, and she was alone and depressed in a new city.

“I didn’t know that I could just drive 15 minutes to go to sunshine,” she told me. She would eventually find serenity in the Sunset and choose to raise her daughter there. Getting to this point however, would be quite the trip.

Sachi is perhaps best known as a surf photographer, but she is also a documentary filmmaker and a professor of journalism at San Francisco State University. As a passionate –– though albeit mediocre –– surfer myself, I was thrilled to meet her. Sachi graduated from the UC Berkeley School of Journalism, where she met her husband, Zach Slobig. The couple would move from Berkeley to Los Angeles, but that wasn’t as far south as they’d go.

In 2011, Sachi and Zach quit their jobs and drove the entire Pacific coast from California to Chile, following the route of a documentary film, 180º South, which Zach previously wrote. They spent 14 months on the road committing to one another, and committing to making a child. Those who know Sachi and Zach’s story know that this trip is where they conceived their daughter Nami, named after the Japanese word for wave.

Sachi is Hapa, half Asian and half white.

“I had a tiger dad, actually,” she tells me, “My white dad was, I think, more the tiger mom of the family.” Sachi’s mom, a nisei Japanese, was born at the Poston War Relocation Camp in Arizona. Her family was incarcerated there during World War II when FDR signed Executive Order 9066 and made Japanese-targeted racism a formal position of the US government.

The Bay Area was one of the regions of the country most impacted by EO 9066, though growing up here I learned close to nothing about it in school. I would drive past Tanforan in San Bruno and never question that it had ever served as anything other than a racetrack. I’ve learned more about this history in the last few years, after learning that the grandfather of my partner, Mike, was also forced into an encampment, like Sachi’s family. Hearing the story of his Jichan –– Japanese for Grandpa –– has brought to life that each of the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were incarcerated then represent not just a statistic, but real people with living relatives who will always have this history as part of their family legacy. Their experiences have taught their families a lot about resilience, but sometimes at a cost. “I feel like I have inherited some of the trauma even though I didn’t live it,” Sachi tells me, “Technically when my mom was born I was an egg in her belly, so I personally think that the trauma from that whole [time]… it’s in me.”

“To speak about our mental health seems to suggest a self-centeredness, a lack of stoicism, and ultimately a form of weakness that creates dissonance with both our Asian cultural values and the persistent myth of the model minority.”

Sachi’s mother, Mitsuko, was the third child of grandma Kiyoko. Her older sisters Hatsuko and Etsuko were kids when the family entered the Poston camp. Kiyoko gave birth to both Mistuko and a younger brother, Tebo, at Poston. After incarceration, the three daughters would go by Americanized versions of their names, Mary, Betty, and Mitzi, respectively. Tebo didn’t have to change his name, as two syllable names seemed easier for Americans to pronounce. This is part of why Sachi is named Sachi (and coincidentally, is also why my own siblings and I all have two syllable names as well). It was only later in life, as the sisters embraced a more activist relationship to their experiences at Poston, that they went back to using their Japanese names.

Many survivors of the incarceration camps have been traditionally hesitant to talk about their experiences, but the younger generations seem to crave their truths. As Sachi explained, “I think my interest in journalism and documentary filmmaking was about trying to capture some of these stories and help people tell these stories in a way my mom and her family and that whole generation really wasn’t encouraged to do.”

It may be the impact of that silence that has inspired Sachi to speak out about her Bipolar I diagnosis. “Asian Americans don’t often have a chance to talk about mental health,” Sachi says. As a South Asian who has grappled with anxiety and depression myself, I can relate to this sentiment. To speak about our mental health seems to suggest a self-centeredness, a lack of stoicism, and ultimately a form of weakness that creates dissonance with both our Asian cultural values and the persistent myth of the model minority.

As it turns out, Sachi’s Bipolar is the real reason she and Zach took that road trip. At the time, the traditional psychiatric medications were interfering with their ability to conceive, and everything else had brutal side effects. Sachi was working at the Los Angeles Times, and the pace and demands of the job were unrelenting; managing her mental health on top of it all was trying.

“I basically couldn’t live with any of the alternative medications” she told me, “so I was just like f– it, the only way this is going to happen is if I’m off of medication, and if I’m off of medication the only way I’m going to stay sane is if I don’t have this job and if I’m in the ocean everyday.” The trip came with its own new set of stressors –– in Nicaragua, for example, they were held up at gunpoint –– but being in the ocean was a profound form of therapy.

Sachi believes that her passion for surfing is partly her body’s response to her Bipolar. Sachi has discussed this with a friend of hers, Faraha Huq, who founded Brown Girl Surf, an Oakland-based nonprofit that exists to increase access to surfing and build a community of women of color surfers. Faraha explained how surfing in cold water –– and really, where is colder than Ocean Beach? –– is one of the most powerful mental health therapies because of the way the water temperature activates your amygdala.

As she tells me this, I wonder if this is part of why I keep coming back to the water myself, even as I dread putting on my thick wetsuit. Perhaps it is the water itself, as much as the flow state of gliding along the power of a wave, that creates healing. Many people look at the photos Sachi takes at big waves like Mavericks and think it’s wild for her to be in that water, but those people are getting it precisely backwards.

“People think I’m crazy and that it’s so scary, but the reality is that nothing is as scary as the darkest corners of my mind. To be in the ocean is actually a relief.”

Sachi is currently working on a feature-length documentary film called SheChange, which tells the story of four female big wave surfers –– who happen to be Sachi’s friends and surf partners –– who are fighting for gender equity in their sport. When I ask her what’s next, she mentions telling more stories about mental health. Her experience as a biracial woman also draws her to stories that celebrate difference.

For the most part, though, the plan seems to be to let life wash over her like the undertow: “I kind of feel like I’m at that point where I was 10 years ago when I took off on my road trip. We took off on this path unknown and things came to us. I kind of feel like that’s where I’m at right now.”

—

Sachi Cunningham is a multi-media journalist, filmmaker, and Assistant Professor at San Francisco State University. sachicunningham.com / IG @seasachi

Published November 2020